9 Functionals

Attaching the needed libraries:

9.1 My first functional: map() (Exercises 9.2.6)

Q1. Use as_mapper() to explore how purrr generates anonymous functions for the integer, character, and list helpers. What helper allows you to extract attributes? Read the documentation to find out.

A1. Let’s handle the two parts of the question separately.

-

as_mapper()and purrr-generated anonymous functions:

Looking at the experimentation below with map() and as_mapper(), we can see that, depending on the type of the input, as_mapper() creates an extractor function using pluck().

# mapping by position -----------------------

x <- list(1, list(2, 3, list(1, 2)))

map(x, 1)

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 1

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 2

as_mapper(1)

#> function (x, ...)

#> pluck_raw(x, list(1), .default = NULL)

#> <environment: 0x558f59718a00>

map(x, list(2, 1))

#> [[1]]

#> NULL

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 3

as_mapper(list(2, 1))

#> function (x, ...)

#> pluck_raw(x, list(2, 1), .default = NULL)

#> <environment: 0x558f59792620>

# mapping by name -----------------------

y <- list(

list(m = "a", list(1, m = "mo")),

list(n = "b", list(2, n = "no"))

)

map(y, "m")

#> [[1]]

#> [1] "a"

#>

#> [[2]]

#> NULL

as_mapper("m")

#> function (x, ...)

#> pluck_raw(x, list("m"), .default = NULL)

#> <environment: 0x558f5984f7c8>

# mixing position and name

map(y, list(2, "m"))

#> [[1]]

#> [1] "mo"

#>

#> [[2]]

#> NULL

as_mapper(list(2, "m"))

#> function (x, ...)

#> pluck_raw(x, list(2, "m"), .default = NULL)

#> <environment: 0x558f598d1730>

# compact functions ----------------------------

map(y, ~ length(.x))

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 2

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 2

as_mapper(~ length(.x))

#> <lambda>

#> function (..., .x = ..1, .y = ..2, . = ..1)

#> length(.x)

#> attr(,"class")

#> [1] "rlang_lambda_function" "function"- You can extract attributes using

purrr::attr_getter():

pluck(Titanic, attr_getter("class"))

#> [1] "table"Q2. map(1:3, ~ runif(2)) is a useful pattern for generating random numbers, but map(1:3, runif(2)) is not. Why not? Can you explain why it returns the result that it does?

A2. As shown by as_mapper() outputs below, the second call is not appropriate for generating random numbers because it translates to pluck() function where the indices for plucking are taken to be randomly generated numbers, and these are not valid accessors and so we get NULLs in return.

map(1:3, ~ runif(2))

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 0.2180892 0.9876342

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 0.3484619 0.3810470

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [1] 0.02098596 0.74972687

as_mapper(~ runif(2))

#> <lambda>

#> function (..., .x = ..1, .y = ..2, . = ..1)

#> runif(2)

#> attr(,"class")

#> [1] "rlang_lambda_function" "function"

map(1:3, runif(2))

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 1

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 2

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [1] 3

as_mapper(runif(2))

#> function (x, ...)

#> pluck_raw(x, list(0.597890264587477, 0.587997315218672), .default = NULL)

#> <environment: 0x558f57ab10a0>Q3. Use the appropriate map() function to:

a) Compute the standard deviation of every column in a numeric data frame.

a) Compute the standard deviation of every numeric column in a mixed data frame. (Hint: you'll need to do it in two steps.)

a) Compute the number of levels for every factor in a data frame.A3. Using the appropriate map() function to:

- Compute the standard deviation of every column in a numeric data frame:

map_dbl(mtcars, sd)

#> mpg cyl disp hp drat

#> 6.0269481 1.7859216 123.9386938 68.5628685 0.5346787

#> wt qsec vs am gear

#> 0.9784574 1.7869432 0.5040161 0.4989909 0.7378041

#> carb

#> 1.6152000- Compute the standard deviation of every numeric column in a mixed data frame:

keep(iris, is.numeric) %>%

map_dbl(sd)

#> Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width

#> 0.8280661 0.4358663 1.7652982 0.7622377- Compute the number of levels for every factor in a data frame:

modify_if(dplyr::starwars, is.character, as.factor) %>%

keep(is.factor) %>%

map_int(~ length(levels(.)))

#> name hair_color skin_color eye_color sex

#> 87 11 31 15 4

#> gender homeworld species

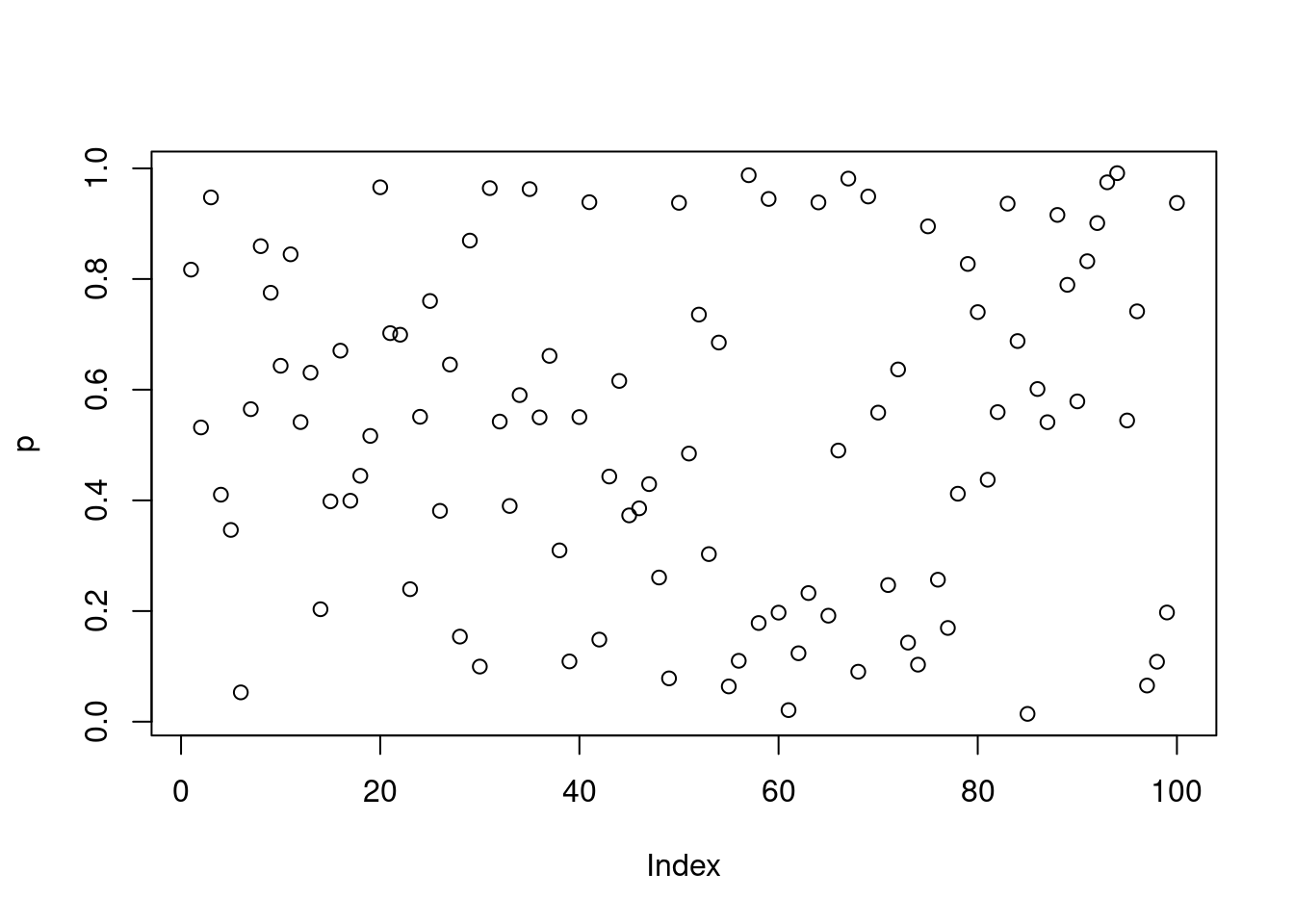

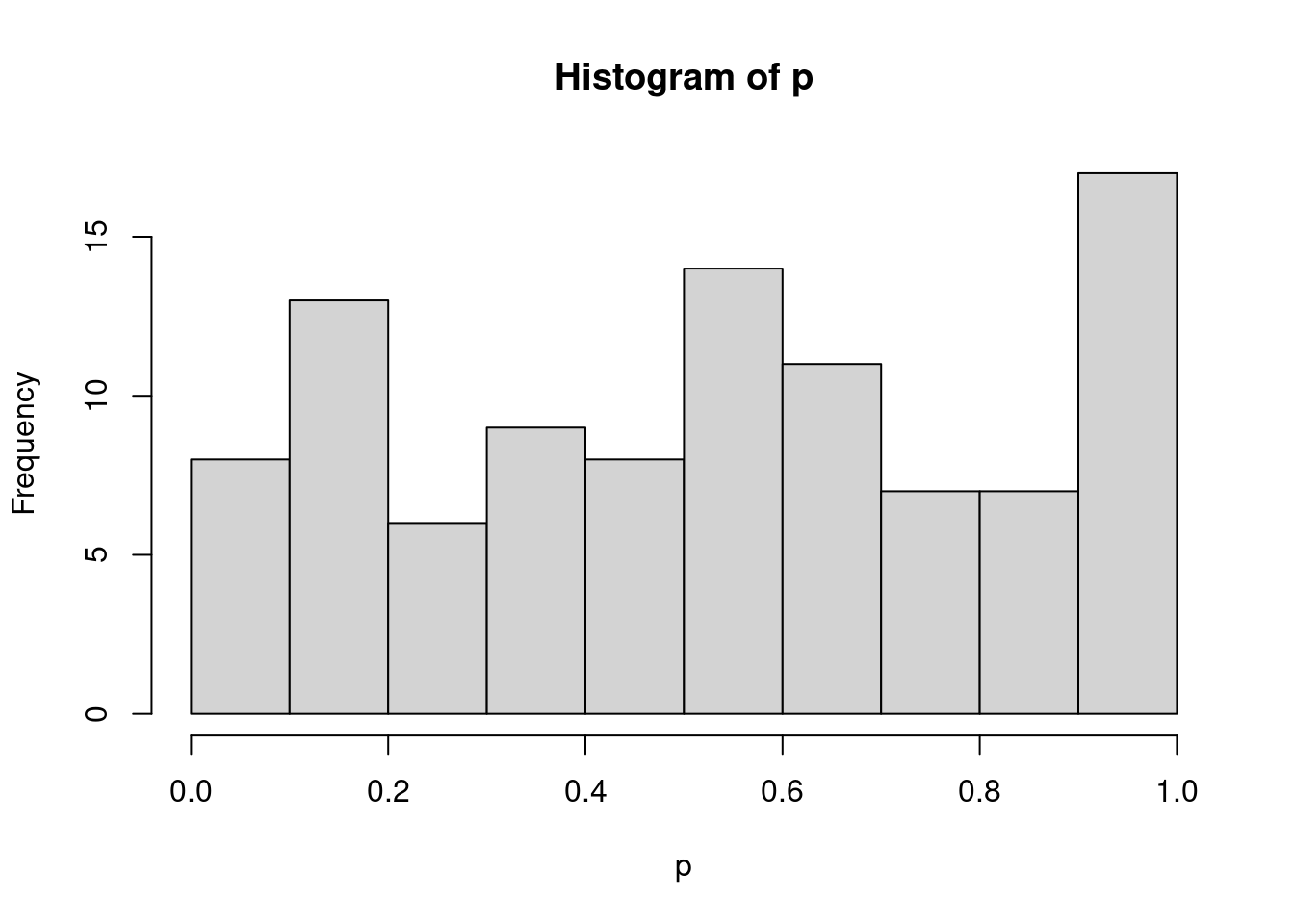

#> 2 48 37Q4. The following code simulates the performance of a t-test for non-normal data. Extract the p-value from each test, then visualise.

A4.

- Extract the p-value from each test:

trials <- map(1:100, ~ t.test(rpois(10, 10), rpois(7, 10)))

(p <- map_dbl(trials, "p.value"))

#> [1] 0.81695628 0.53177360 0.94750819 0.41026769 0.34655294

#> [6] 0.05300287 0.56479901 0.85936864 0.77517391 0.64321161

#> [11] 0.84462914 0.54144946 0.63070476 0.20325827 0.39824435

#> [16] 0.67052432 0.39932663 0.44437632 0.51645941 0.96578745

#> [21] 0.70219557 0.69931716 0.23946786 0.55100566 0.76028958

#> [26] 0.38105366 0.64544126 0.15379307 0.86945196 0.09965658

#> [31] 0.96425489 0.54239108 0.38985789 0.59019282 0.96247907

#> [36] 0.54997487 0.66111391 0.30961551 0.10897334 0.55049635

#> [41] 0.93882405 0.14836866 0.44307287 0.61583610 0.37284284

#> [46] 0.38559622 0.42935767 0.26059293 0.07831619 0.93768396

#> [51] 0.48459268 0.73571291 0.30288560 0.68521609 0.06374636

#> [56] 0.11007808 0.98758443 0.17831882 0.94471538 0.19711729

#> [61] 0.02094185 0.12370745 0.23247837 0.93842382 0.19160550

#> [66] 0.49005550 0.98146240 0.09034183 0.94912080 0.55857523

#> [71] 0.24692070 0.63658206 0.14290966 0.10309770 0.89516449

#> [76] 0.25660092 0.16943034 0.41199780 0.82721280 0.74017418

#> [81] 0.43724631 0.55944024 0.93615100 0.68788872 0.01416627

#> [86] 0.60120497 0.54125910 0.91581929 0.78949327 0.57887371

#> [91] 0.83217542 0.90108906 0.97474727 0.99129282 0.54436155

#> [96] 0.74159859 0.06534957 0.10834529 0.19737786 0.93750342- Visualise the extracted p-values:

plot(p)

hist(p)

Q5. The following code uses a map nested inside another map to apply a function to every element of a nested list. Why does it fail, and what do you need to do to make it work?

x <- list(

list(1, c(3, 9)),

list(c(3, 6), 7, c(4, 7, 6))

)

triple <- function(x) x * 3

map(x, map, .f = triple)

#> Error in `map()`:

#> ℹ In index: 1.

#> Caused by error in `.f()`:

#> ! unused argument (function (.x, .f, ..., .progress = FALSE)

#> {

#> map_("list", .x, .f, ..., .progress = .progress)

#> })A5. This function fails because this call effectively evaluates to the following:

map(.x = x, .f = ~ triple(x = .x, map))But triple() has only one parameter (x), and so the execution fails.

Here is the fixed version:

x <- list(

list(1, c(3, 9)),

list(c(3, 6), 7, c(4, 7, 6))

)

triple <- function(x) x * 3

map(x, .f = ~ map(.x, ~ triple(.x)))

#> [[1]]

#> [[1]][[1]]

#> [1] 3

#>

#> [[1]][[2]]

#> [1] 9 27

#>

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [[2]][[1]]

#> [1] 9 18

#>

#> [[2]][[2]]

#> [1] 21

#>

#> [[2]][[3]]

#> [1] 12 21 18Q6. Use map() to fit linear models to the mtcars dataset using the formulas stored in this list:

A6. Fitting linear models to the mtcars dataset using the provided formulas:

formulas <- list(

mpg ~ disp,

mpg ~ I(1 / disp),

mpg ~ disp + wt,

mpg ~ I(1 / disp) + wt

)

map(formulas, ~ lm(formula = ., data = mtcars))

#> [[1]]

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = ., data = mtcars)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept) disp

#> 29.59985 -0.04122

#>

#>

#> [[2]]

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = ., data = mtcars)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept) I(1/disp)

#> 10.75 1557.67

#>

#>

#> [[3]]

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = ., data = mtcars)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept) disp wt

#> 34.96055 -0.01772 -3.35083

#>

#>

#> [[4]]

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = ., data = mtcars)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept) I(1/disp) wt

#> 19.024 1142.560 -1.798Q7. Fit the model mpg ~ disp to each of the bootstrap replicates of mtcars in the list below, then extract the \(R^2\) of the model fit (Hint: you can compute the \(R^2\) with summary().)

bootstrap <- function(df) {

df[sample(nrow(df), replace = TRUE), , drop = FALSE]

}

bootstraps <- map(1:10, ~ bootstrap(mtcars))A7. This can be done using map_dbl():

bootstrap <- function(df) {

df[sample(nrow(df), replace = TRUE), , drop = FALSE]

}

bootstraps <- map(1:10, ~ bootstrap(mtcars))

bootstraps %>%

map(~ lm(mpg ~ disp, data = .x)) %>%

map(summary) %>%

map_dbl("r.squared")

#> [1] 0.7864562 0.8110818 0.7956331 0.7632399 0.7967824

#> [6] 0.7364226 0.7203027 0.6653252 0.7732780 0.67533299.2 Map variants (Exercises 9.4.6)

Q1. Explain the results of modify(mtcars, 1).

A1. modify() returns the object of type same as the input. Since the input here is a data frame of certain dimensions and .f = 1 translates to plucking the first element in each column, it returns a data frame with the same dimensions with the plucked element recycled across rows.

head(modify(mtcars, 1))

#> mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

#> 1 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4

#> 2 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4

#> 3 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4

#> 4 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4

#> 5 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4

#> 6 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4Q2. Rewrite the following code to use iwalk() instead of walk2(). What are the advantages and disadvantages?

cyls <- split(mtcars, mtcars$cyl)

paths <- file.path(temp, paste0("cyl-", names(cyls), ".csv"))

walk2(cyls, paths, write.csv)A2. Let’s first rewrite provided code using iwalk():

cyls <- split(mtcars, mtcars$cyl)

names(cyls) <- file.path(temp, paste0("cyl-", names(cyls), ".csv"))

iwalk(cyls, ~ write.csv(.x, .y))The advantage of using iwalk() is that we need to now deal with only a single variable (cyls) instead of two (cyls and paths).

The disadvantage is that the code is difficult to reason about:

In walk2(), it’s explicit what .x (= cyls) and .y (= paths) correspond to, while this is not so for iwalk() (i.e., .x = cyls and .y = names(cyls)) with the .y argument being “invisible”.

Q3. Explain how the following code transforms a data frame using functions stored in a list.

trans <- list(

disp = function(x) x * 0.0163871,

am = function(x) factor(x, labels = c("auto", "manual"))

)

nm <- names(trans)

mtcars[nm] <- map2(trans, mtcars[nm], function(f, var) f(var))Compare and contrast the map2() approach to this map() approach:

mtcars[nm] <- map(nm, ~ trans[[.x]](mtcars[[.x]]))A3. map2() supplies the functions stored in trans as anonymous functions via placeholder f, while the names of the columns specified in mtcars[nm] are supplied as var argument to the anonymous function. Note that the function is iterating over indices for vectors of transformations and column names.

trans <- list(

disp = function(x) x * 0.0163871,

am = function(x) factor(x, labels = c("auto", "manual"))

)

nm <- names(trans)

mtcars[nm] <- map2(trans, mtcars[nm], function(f, var) f(var))In the map() approach, the function is iterating over indices for vectors of column names.

mtcars[nm] <- map(nm, ~ trans[[.x]](mtcars[[.x]]))The latter approach can’t afford passing arguments to placeholders in an anonymous function.

Q4. What does write.csv() return, i.e. what happens if you use it with map2() instead of walk2()?

A4. If we use map2(), it will work, but it will print NULLs to the console for every list element.

withr::with_tempdir(

code = {

ls <- split(mtcars, mtcars$cyl)

nm <- names(ls)

map2(ls, nm, write.csv)

}

)

#> $`4`

#> NULL

#>

#> $`6`

#> NULL

#>

#> $`8`

#> NULL9.3 Predicate functionals (Exercises 9.6.3)

Q1. Why isn’t is.na() a predicate function? What base R function is closest to being a predicate version of is.na()?

A1. As mentioned in the docs:

A predicate is a function that returns a single

TRUEorFALSE.

The is.na() function does not return a logical scalar, but instead returns a vector and thus isn’t a predicate function.

# contrast the following behavior of predicate functions

is.character(c("x", 2))

#> [1] TRUE

is.null(c(3, NULL))

#> [1] FALSE

# with this behavior

is.na(c(NA, 1))

#> [1] TRUE FALSEThe closest equivalent of a predicate function in base-R is anyNA() function.

Q2. simple_reduce() has a problem when x is length 0 or length 1. Describe the source of the problem and how you might go about fixing it.

simple_reduce <- function(x, f) {

out <- x[[1]]

for (i in seq(2, length(x))) {

out <- f(out, x[[i]])

}

out

}A2. The supplied function struggles with inputs of length 0 and 1 because function tries to subscript out-of-bound values.

simple_reduce(numeric(), sum)

#> Error in `x[[1]]`:

#> ! subscript out of bounds

simple_reduce(1, sum)

#> Error in `x[[i]]`:

#> ! subscript out of bounds

simple_reduce(1:3, sum)

#> [1] 6This problem can be solved by adding init argument, which supplies the default or initial value:

simple_reduce2 <- function(x, f, init = 0) {

# initializer will become the first value

if (length(x) == 0L) {

return(init)

}

if (length(x) == 1L) {

return(x[[1L]])

}

out <- x[[1]]

for (i in seq(2, length(x))) {

out <- f(out, x[[i]])

}

out

}Let’s try it out:

simple_reduce2(numeric(), sum)

#> [1] 0

simple_reduce2(1, sum)

#> [1] 1

simple_reduce2(1:3, sum)

#> [1] 6Depending on the function, we can provide a different init argument:

simple_reduce2(numeric(), `*`, init = 1)

#> [1] 1

simple_reduce2(1, `*`, init = 1)

#> [1] 1

simple_reduce2(1:3, `*`, init = 1)

#> [1] 6Q3. Implement the span() function from Haskell: given a list x and a predicate function f, span(x, f) returns the location of the longest sequential run of elements where the predicate is true. (Hint: you might find rle() helpful.)

A3. Implementation of span():

span <- function(x, f) {

running_lengths <- purrr::map_lgl(x, ~ f(.x)) %>% rle()

df <- dplyr::tibble(

"lengths" = running_lengths$lengths,

"values" = running_lengths$values

) %>%

dplyr::mutate(rowid = dplyr::row_number()) %>%

dplyr::filter(values)

# no sequence where condition is `TRUE`

if (nrow(df) == 0L) {

return(integer())

}

# only single sequence where condition is `TRUE`

if (nrow(df) == 1L) {

return((df$rowid):(df$lengths - 1 + df$rowid))

}

# multiple sequences where condition is `TRUE`; select max one

if (nrow(df) > 1L) {

df <- dplyr::filter(df, lengths == max(lengths))

return((df$rowid):(df$lengths - 1 + df$rowid))

}

}Testing it once:

span(c(0, 0, 0, 0, 0), is.na)

#> integer(0)

span(c(NA, 0, NA, NA, NA), is.na)

#> [1] 3 4 5

span(c(NA, 0, 0, 0, 0), is.na)

#> [1] 1

span(c(NA, NA, 0, 0, 0), is.na)

#> [1] 1 2Testing it twice:

span(c(3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6), function(x) x > 3)

#> [1] 2 3 4

span(c(3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6), function(x) x > 9)

#> integer(0)

span(c(3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6), function(x) x == 3)

#> [1] 1

span(c(3, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6), function(x) x %in% c(2, 4))

#> [1] 2 3Q4. Implement arg_max(). It should take a function and a vector of inputs, and return the elements of the input where the function returns the highest value. For example, arg_max(-10:5, function(x) x ^ 2) should return -10. arg_max(-5:5, function(x) x ^ 2) should return c(-5, 5). Also implement the matching arg_min() function.

A4. Here are implementations for the specified functions:

- Implementing

arg_max()

arg_max <- function(.x, .f) {

df <- dplyr::tibble(

original = .x,

transformed = purrr::map_dbl(.x, .f)

)

dplyr::filter(df, transformed == max(transformed))[["original"]]

}

arg_max(-10:5, function(x) x^2)

#> [1] -10

arg_max(-5:5, function(x) x^2)

#> [1] -5 5- Implementing

arg_min()

arg_min <- function(.x, .f) {

df <- dplyr::tibble(

original = .x,

transformed = purrr::map_dbl(.x, .f)

)

dplyr::filter(df, transformed == min(transformed))[["original"]]

}

arg_min(-10:5, function(x) x^2)

#> [1] 0

arg_min(-5:5, function(x) x^2)

#> [1] 0Q5. The function below scales a vector so it falls in the range [0, 1]. How would you apply it to every column of a data frame? How would you apply it to every numeric column in a data frame?

scale01 <- function(x) {

rng <- range(x, na.rm = TRUE)

(x - rng[1]) / (rng[2] - rng[1])

}A5. We will use purrr package to apply this function. Key thing to keep in mind is that a data frame is a list of atomic vectors of equal length.

- Applying function to every column in a data frame: We will use

anscombeas example since it has all numeric columns.

purrr::map_df(head(anscombe), .f = scale01)

#> # A tibble: 6 × 8

#> x1 x2 x3 x4 y1 y2 y3 y4

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 0.333 0.333 0.333 NaN 0.362 0.897 0.116 0.266

#> 2 0 0 0 NaN 0 0.0345 0 0

#> 3 0.833 0.833 0.833 NaN 0.209 0.552 1 0.633

#> 4 0.167 0.167 0.167 NaN 0.618 0.578 0.0570 1

#> 5 0.5 0.5 0.5 NaN 0.458 1 0.174 0.880

#> 6 1 1 1 NaN 1 0 0.347 0.416- Applying function to every numeric column in a data frame: We will use

irisas example since not all of its columns are of numeric type.

purrr::modify_if(head(iris), .p = is.numeric, .f = scale01)

#> Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species

#> 1 0.625 0.5555556 0.25 0 setosa

#> 2 0.375 0.0000000 0.25 0 setosa

#> 3 0.125 0.2222222 0.00 0 setosa

#> 4 0.000 0.1111111 0.50 0 setosa

#> 5 0.500 0.6666667 0.25 0 setosa

#> 6 1.000 1.0000000 1.00 1 setosa9.4 Base functionals (Exercises 9.7.3)

Q1. How does apply() arrange the output? Read the documentation and perform some experiments.

A1. Let’s prepare an array and apply a function over different margins:

(m <- as.array(table(mtcars$cyl, mtcars$am, mtcars$vs)))

#> , , = 0

#>

#>

#> auto manual

#> 4 0 1

#> 6 0 3

#> 8 12 2

#>

#> , , = 1

#>

#>

#> auto manual

#> 4 3 7

#> 6 4 0

#> 8 0 0

# rows

apply(m, 1, function(x) x^2)

#>

#> 4 6 8

#> [1,] 0 0 144

#> [2,] 1 9 4

#> [3,] 9 16 0

#> [4,] 49 0 0

# columns

apply(m, 2, function(x) x^2)

#>

#> auto manual

#> [1,] 0 1

#> [2,] 0 9

#> [3,] 144 4

#> [4,] 9 49

#> [5,] 16 0

#> [6,] 0 0

# rows and columns

apply(m, c(1, 2), function(x) x^2)

#> , , = auto

#>

#>

#> 4 6 8

#> 0 0 0 144

#> 1 9 16 0

#>

#> , , = manual

#>

#>

#> 4 6 8

#> 0 1 9 4

#> 1 49 0 0As can be seen, apply() returns outputs organised first by the margins being operated over, and only then the results.

Q2. What do eapply() and rapply() do? Does purrr have equivalents?

A2. Let’s consider them one-by-one.

As mentioned in its documentation:

eapply()applies FUN to the named values from an environment and returns the results as a list.

Here is an example:

library(rlang)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'rlang'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:purrr':

#>

#> flatten, flatten_chr, flatten_dbl, flatten_int,

#> flatten_lgl, flatten_raw, invoke, splice

#> The following object is masked from 'package:magrittr':

#>

#> set_names

e <- env("x" = 1, "y" = 2)

rlang::env_print(e)

#> <environment: 0x558f588826f8>

#> Parent: <environment: global>

#> Bindings:

#> • x: <dbl>

#> • y: <dbl>

eapply(e, as.character)

#> $x

#> [1] "1"

#>

#> $y

#> [1] "2"purrr doesn’t have any function to iterate over environments.

rapply()is a recursive version of lapply with flexibility in how the result is structured (how = “..”).

Here is an example:

X <- list(list(a = TRUE, b = list(c = c(4L, 3.2))), d = 9.0)

rapply(X, as.character, classes = "numeric", how = "replace")

#> [[1]]

#> [[1]]$a

#> [1] TRUE

#>

#> [[1]]$b

#> [[1]]$b$c

#> [1] "4" "3.2"

#>

#>

#>

#> $d

#> [1] "9"purrr has something similar in modify_tree().

X <- list(list(a = TRUE, b = list(c = c(4L, 3.2))), d = 9.0)

purrr::modify_tree(X, leaf = length)

#> [[1]]

#> [[1]]$a

#> [1] 1

#>

#> [[1]]$b

#> [[1]]$b$c

#> [1] 2

#>

#>

#>

#> $d

#> [1] 1Q3. Challenge: read about the fixed point algorithm. Complete the exercises using R.

A3. As mentioned in the suggested reading material:

A number \(x\) is called a fixed point of a function \(f\) if \(x\) satisfies the equation \(f(x) = x\). For some functions \(f\) we can locate a fixed point by beginning with an initial guess and applying \(f\) repeatedly, \(f(x), f(f(x)), f(f(f(x))), ...\) until the value does not change very much. Using this idea, we can devise a procedure fixed-point that takes as inputs a function and an initial guess and produces an approximation to a fixed point of the function.

Let’s first implement a fixed-point algorithm:

close_enough <- function(x1, x2, tolerance = 0.001) {

if (abs(x1 - x2) < tolerance) {

return(TRUE)

} else {

return(FALSE)

}

}

find_fixed_point <- function(.f, .guess, tolerance = 0.001) {

.next <- .f(.guess)

is_close_enough <- close_enough(.next, .guess, tolerance = tolerance)

if (is_close_enough) {

return(.next)

} else {

find_fixed_point(.f, .next, tolerance)

}

}Let’s check if it works as expected:

find_fixed_point(cos, 1.0)

#> [1] 0.7387603

# cos(x) = x

cos(find_fixed_point(cos, 1.0))

#> [1] 0.7393039We will solve only one exercise from the reading material. Rest are beyond the scope of this solution manual.

Show that the golden ratio \(\phi\) is a fixed point of the transformation \(x \mapsto 1 + 1/x\), and use this fact to compute \(\phi\) by means of the fixed-point procedure.

golden_ratio_f <- function(x) 1 + (1 / x)

find_fixed_point(golden_ratio_f, 1.0)

#> [1] 1.6181829.5 Session information

sessioninfo::session_info(include_base = TRUE)

#> ─ Session info ───────────────────────────────────────────

#> setting value

#> version R version 4.5.2 (2025-10-31)

#> os Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS

#> system x86_64, linux-gnu

#> ui X11

#> language (EN)

#> collate C.UTF-8

#> ctype C.UTF-8

#> tz UTC

#> date 2026-01-13

#> pandoc 3.8.3 @ /opt/hostedtoolcache/pandoc/3.8.3/x64/ (via rmarkdown)

#> quarto NA

#>

#> ─ Packages ───────────────────────────────────────────────

#> package * version date (UTC) lib source

#> base * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> bookdown 0.46 2025-12-05 [1] RSPM

#> bslib 0.9.0 2025-01-30 [1] RSPM

#> cachem 1.1.0 2024-05-16 [1] RSPM

#> cli 3.6.5 2025-04-23 [1] RSPM

#> compiler 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> datasets * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> digest 0.6.39 2025-11-19 [1] RSPM

#> downlit 0.4.5 2025-11-14 [1] RSPM

#> dplyr 1.1.4 2023-11-17 [1] RSPM

#> emoji 16.0.0 2024-10-28 [1] RSPM

#> evaluate 1.0.5 2025-08-27 [1] RSPM

#> fastmap 1.2.0 2024-05-15 [1] RSPM

#> fs 1.6.6 2025-04-12 [1] RSPM

#> generics 0.1.4 2025-05-09 [1] RSPM

#> glue 1.8.0 2024-09-30 [1] RSPM

#> graphics * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> grDevices * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> htmltools 0.5.9 2025-12-04 [1] RSPM

#> jquerylib 0.1.4 2021-04-26 [1] RSPM

#> jsonlite 2.0.0 2025-03-27 [1] RSPM

#> knitr 1.51 2025-12-20 [1] RSPM

#> lifecycle 1.0.5 2026-01-08 [1] RSPM

#> magrittr * 2.0.4 2025-09-12 [1] RSPM

#> memoise 2.0.1 2021-11-26 [1] RSPM

#> methods * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> pillar 1.11.1 2025-09-17 [1] RSPM

#> pkgconfig 2.0.3 2019-09-22 [1] RSPM

#> purrr * 1.2.1 2026-01-09 [1] RSPM

#> R6 2.6.1 2025-02-15 [1] RSPM

#> rlang * 1.1.7 2026-01-09 [1] RSPM

#> rmarkdown 2.30 2025-09-28 [1] RSPM

#> sass 0.4.10 2025-04-11 [1] RSPM

#> sessioninfo 1.2.3 2025-02-05 [1] RSPM

#> stats * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> stringi 1.8.7 2025-03-27 [1] RSPM

#> stringr 1.6.0 2025-11-04 [1] RSPM

#> tibble 3.3.1 2026-01-11 [1] RSPM

#> tidyselect 1.2.1 2024-03-11 [1] RSPM

#> tools 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> utils * 4.5.2 2025-10-31 [3] local

#> vctrs 0.6.5 2023-12-01 [1] RSPM

#> withr 3.0.2 2024-10-28 [1] RSPM

#> xfun 0.55 2025-12-16 [1] RSPM

#> xml2 1.5.1 2025-12-01 [1] RSPM

#> yaml 2.3.12 2025-12-10 [1] RSPM

#>

#> [1] /home/runner/work/_temp/Library

#> [2] /opt/R/4.5.2/lib/R/site-library

#> [3] /opt/R/4.5.2/lib/R/library

#> * ── Packages attached to the search path.

#>

#> ──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────